U.S. Plans

Where do you see yourself in five years? Ten? At FMi, our goal is to provide you with the most current information and the best tools – everything you need to plan your retirement, regardless of your type of investment. From our exclusive Retirement Zone newsletter to an online review of our investors' most frequently asked questions, FMi keeps you up-to-date and on your proper "savings track," allowing you to make informed decisions and build a better retirement strategy for the years ahead. Whatever your savings goal – supplementing Social Security, combining retirement incomes, setting up the next generation or just ensuring a comfortable retirement – FMi will help you craft the right action plan, monitor your performance and adjust your investments accordingly … everything we can do to help you achieve your dreams.

General FAQ's - Answers

Before you can determine how much money you'll need for a comfortable retirement lifestyle, you need to think about how you plan to spend your money in retirement. Remember, retirement won't free you from ongoing expenses. You'll still have to budget for items such as food, clothing, utilities, and car expenses. And while some expenses will decrease as you approach retirement-mortgage payments, for example-other expenses will likely increase. For instance, you may spend more money on medical insurance and health care, as well as entertainment, recreation, and travel.

Because people today are living longer, most retirees will be spending more time in retirement than did their parents and grandparents. You may need your retirement income to last for 15 to 20 years or more. This means you'll need roughly 70 to 80 percent of your pre-retirement income to afford a comfortable lifestyle. So it's a good idea to start thinking now about your future expenses.

When you retire, you'll most likely receive your income from more than one source. There's Social Security (US) or Social Insurance (Bermuda) and maybe income from your personal savings or investments. But, like so many of us, you may need an additional source of income to achieve financial security in retirement. Your company's retirement plan is an invaluable resource that can help make your future free of financial worries.

When it comes to saving for retirement, time is money-the sooner you start, the more you save. If you start early, you have more time to make the power of compounding work for you. Compounding means that the interest on your savings or investments is earning interest. For example, let's say you start by investing $1,000. Assuming a 5 percent interest rate, you would have $1,050 by the end of the year. That means you'll be earning interest on $1,050 during the next year. If you get a 5 percent return on this $1,050, you will add another $52.50 to your account, bringing your total up to $1,102.50. After 3 years your account would be worth $1,157.63, 4 years $1,215.51, 5 years $1,276.28, and so forth. So you can see how the value of your original investment will increase exponentially over time.

The longer you delay saving for retirement, the harder it becomes to accumulate enough money. Saving gradually over many years is much easier than trying to catch up by saving a lot in a short time later in your career.

Inflation is a general increase in the price of goods and services over time. Simply put, it makes everything you buy more expensive. To ensure a comfortable retirement lifestyle, you need to allow for a higher cost of living due to inflation when you estimate your annual income needs for retirement.

There are two general types of retirement plans: defined benefit (DB) plans and defined contribution (DC) plans. In the US, these are tax-deferred programs, meaning that you don't pay taxes on any of the money that goes into your account--including the interest your money earns--until you withdraw the money, usually after you retire.

Bermuda's National Pension Scheme (Occupational Pensions) Act of 1998 mandates the establishment of private occupational retirement schemes (also referred to as employer-sponsored pension schemes) operating under specific regulations and appropriate supervision. An employer-sponsored plan may be a defined benefit (DB) or defined contribution (DC) arrangement.

A defined benefit plan (for example, a pension plan) promises to pay a specific amount of money each month when you retire-in other words, the plan defines the benefit you will receive upon retirement. DB plans include a formula that is used to calculate the benefit amount according to how many years you've worked for the company and how much money you've earned over all or part of the employment relationship. In most cases, you do not contribute money to a defined benefit plan-the plan is funded by your employer's contributions. This means that your employer decides how to invest the money, and keeps any gains or absorbs any losses over time.

Defined benefit plans are most profitable for employees who work for one company for many years, since the benefit amount is determined, in part, by years of service. But what are the options for workers who change jobs several times during their careers and would receive only moderate benefits from DB plans? The increasing tendency of workers not to remain at one workplace for all of their careers has created the need for another type of retirement plan--the defined contribution plan.

In a defined contribution plan, the amount of money that's contributed to your account is defined, rather than the benefit you'll receive upon retirement. A defined contribution plan pays you based on how much you and/or your employer contribute, how long you and/or your employer contribute, and how the contributions are invested. This means that you can accumulate funds for your retirement even if you're with a particular company for only a few years.

In the United States, there are three main types of defined contribution plans: profit-sharing plans, 401(k)s, and 403(b)s. In a profit-sharing plan, you share in your employer's profits; you do not contribute money to the plan. In a 401(k) plan, you make contributions to your own account; your employer is not required to match your contributions. 403(b)s are similar to 401(k)s, but they are offered only to employees of K-12 public schools and certain non-profit organizations.

A profit-sharing plan is program sponsored by your employer that enables you to share in the company's profits. Your employer decides how much money will be contributed to the plan each year, and a formula within the plan determines how the money will be distributed among the employees' individual accounts. Most likely, your employer will also decide how the contributions will be invested, although in some cases employees do have a say in investment decisions.

The amount of money you will receive from your employer's profit-sharing plan is not fixed. Rather, your benefit is the sum of all contributions to the plan, plus or minus any gains or losses on investments. When you withdraw the money at retirement, you will have to pay taxes on the amount you take out of your account.

The term 401(k) comes from the section of the Internal Revenue Service tax code that allows employees of qualified companies to set aside funds for retirement. 401(k)s provide an incentive for employees to save for retirement by offering special tax advantages. Essentially, the plan enables you to contribute a percentage of your paycheck to your 401(k) account before your paycheck is taxed, and you do not pay taxes on the money as long as it remains in your account.

Section 403(b) of the Internal Revenue Service tax code allows employees of certain non-profit organizations-hospitals, colleges and universities, research institutes, libraries, and so forth-and K-12 public schools to set aside funds for retirement. 403(b)s provide an incentive for employees to save for retirement by offering special tax advantages. Essentially, the plan enables you to contribute a percentage of your paycheck to your 403(b) account before your paycheck is taxed, and you do not pay taxes on the money as long as it remains in your account.

In the US, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), passed in 1974, protects employees' rights when it comes to their retirement benefits. Basically, ERISA establishes the rules that employers must follow in providing retirement plans to their employees. ERISA and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Tax Code specify how all retirement plans operate in the United States.

In Bermuda, the Pension Commission ensures that all pension plans are being run according to law. The Minister of Finance appoints the chairman, deputy chairman, and at least five other members who make up the Commission. It's the Commission's responsibility to verify that payments of benefits are made and to investigate complaints. The Commission can refuse to register a pension plan, amend a pension plan, or revoke the registration of a pension plan that does not conform to the law.

The Department of Labor's Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) is the federal law that sets minimum standards for operating most voluntary established tax qualified retirement plans to provide protection for individuals who participate in the plans.

US Qualified Plans

In a 401(k) plan, you decide how much money you want to contribute to your account each pay period. This is what's known as your salary deferral amount. Contributions are automatically deducted from your paycheck before taxes are taken out. You choose the funds you want to invest in from the options offered by your employer. Interest and earnings are free from taxes as long as the money remains in your account, so you have more real dollars working for you. When you withdraw the money--usually at retirement--you will have to pay taxes on the amount you take out of your account.

Although the money in your 401(k) account belongs to you, it isn't yours to spend. Remember, the point of participating in a 401(k) plan is to save for retirement, so the money is supposed to remain in your account until you're at least 59 ½ years old (past the early retirement penalty age). Your company's plan may allow you to take a loan from your account under certain circumstances, in which case you pay back the principal and current interest rates to your account over a set term. Some plans also allow for withdrawals under conditions of financial hardship. You should consider a hardship withdrawal only as a last resort, because this type of early withdrawal usually comes along with some financial penalties. (See "When can I withdraw money from my 401(k)?" below.)

Participating in a 401(k) plan is one of the best investments you can make in your future. Consider the following benefits:

- Your money grows in a tax-deferred environment. As long as your contributions remain in your 401(k) account, you don't have to worry about taxes taking a bite out of your retirement funds. Your account balance grows more quickly as a result.

- Your taxable income is reduced by your contributions. Because your contributions are automatically deducted from your paycheck before taxes are taken out, you'll be taxed on a smaller gross income. This means you won't have to pay as much in income tax.

- Your employer may make matching contributions to your 401(k). In some cases, employers make dollar-for-dollar contributions, but a more common match is $.50 for every dollar an employee contributes. Whatever amount your employer agrees upon is money on top of your salary. However, this money does not belong to you right away. You have to be 100 percent vested to have full ownership of your employer's contributions. You are 100 percent vested immediately in the money you contribute to your account.

- You decide how to invest your money. A typical 401(k) plan offers participants a number of investment options from which to choose. As a participant, you can decide how to divide your total contribution among the various investments.

- You can take the plan with you if you change jobs. If you decide to leave your current employer, you can take your 401(k) money with you. You may decide to make a rollover contribution into your new employer's 401(k) plan, or you may deposit the money into an Individual Retirement Account. Either way you'll avoid early withdrawal penalties.

- It's easy to keep track of the savings in your 401(k) account. You'll receive periodic statements from your employer that show your account balance, contributions, and any gains or losses on your investments. That way it's easy to keep an eye on how your retirement funds are growing.

Employees are usually eligible to participate in their employer's 401(k) plan if they are full-time salaried or full-time hourly workers over 21 years of age. It's not uncommon, however, for employers to delay eligibility for new employees. More often than not, new employees must work for a company for a specified period of time before they can participate in the company's plan, because employees who are going to leave generally do so during their first year of employment. It makes sense that employers are more willing to extend benefits to employees who are planning to stay on a while.

Some companies will allow you to participate right away, if you're eligible, but may make you wait for some time before you're eligible for the company match. Other companies set a specific date for entry into the plan.

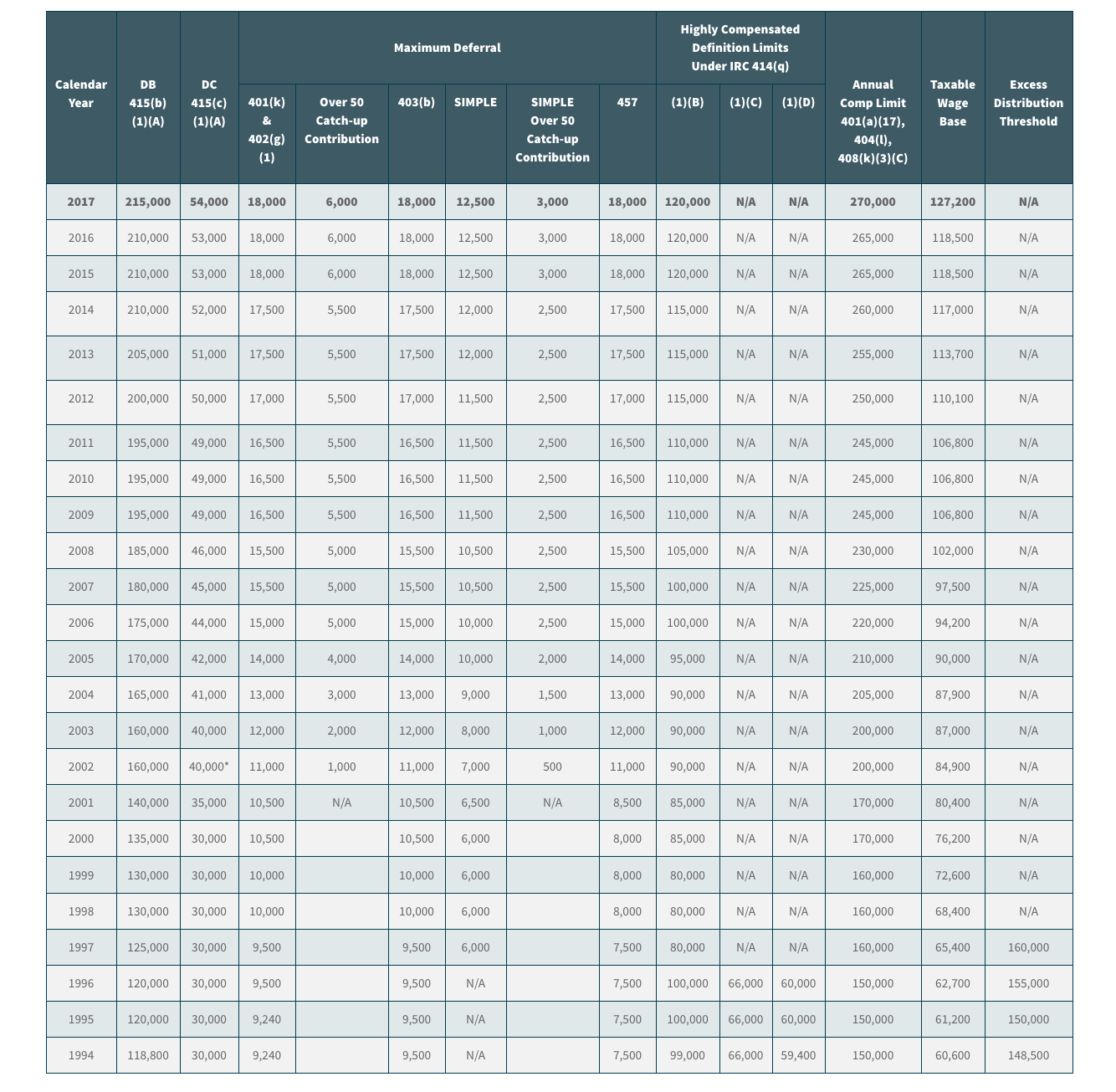

Although every company's 401(k) plan is different, the IRS imposes standard regulations on all plans. For example, the IRS limits the total amount of your pre-tax contributions over the year. The limit for the year 2013 is $17,500, which does not include any matching contributions made to your account by your employer. Additionally, total contributions--yours and your employer's--to all defined contribution plans cannot exceed the lesser amount of $51,000 or 25 percent of your gross pay each year.

The IRS also imposes limits on contributions made by highly compensated employees (HCEs)--those employees who are paid $115,000 or more a year or who have at least 5 percent ownership in the company. If you're considered an HCE, you may be limited to contributions totaling as little as 6 percent of your salary, which is far below the $17,000 limit. Why is this? When the 401(k) rules were first laid out, the government was afraid that non-highly compensated employees (NHCEs)--often referred to as "rank-and-file" employees--would not participate, and that HCEs would be the only employees profiting from 401(k)s. To ensure that rank-and-file employees would receive the same benefits under 401(k) plans as HCEs, Congress made the IRS responsible for devising a way to test each plan. Because the test is designed to protect non-highly compensated employees against discrimination, the testing process is known as non-discrimination testing. In a nutshell, non-discrimination testing ensures that highly compensated employees as a group don't contribute more than 2 percent of pay more than the lower compensated employees as a group do.

Your company's 401(k) plan may allow you to take a loan from your account, usually up to one-half of your total vested account, not to exceed $50,000. You pay your account back the amount you borrowed, plus interest, through automatic deductions from your pay or bank account. Typically, employees are allowed five years to repay loans, and no taxes or penalties are incurred as long as the loan is repaid on time.

What if you leave your company before you've repaid the loan in full? If your company's plan is like most, you'll have to repay the outstanding balance within a certain time frame, usually 30 to 90 days. If you don't repay your loan within this time frame, the loan is treated as a withdrawal, which is taxable. Not only must you pay current income taxes on the withdrawal, you may also be subject to a 10 percent early withdrawal penalty to the government.

Before you decide to take a loan from your account, you should consider how this will affect your retirement funds in the long term. Remember, the money can't grow for you if it's not in your account.

Participants in a 401(k) plan typically choose their investments from a menu of mutual funds offered in the plan. Mutual funds contain investments such as stocks, bonds, and money market funds. When you buy shares in a mutual fund, you invest in all the securities (investments) in that fund. It's up to you to divide your money among the securities within the fund.

You don't need to be an investment professional to be a successful investor--but you do need to know some basic investment principles. Let's take a closer look at stocks, bonds, and money market funds:

Stocks. Stocks give you an ownership interest in the company issuing the investment. The value of an individual stock varies up or down with changes in its issuing company, the stock market in general, and the economy. Stocks offer the highest potential investment returns among retirement plan investments, but they are also the investment type with the most risk of losing the amount invested, or principal.

Bonds. Bonds are loans issued by corporations, a local or state government, or the federal government. When you buy a bond you are, in effect, lending money to the issuer. The bond issuer pays you a set interest rate over a set term. At the end of the bond's term (maturity), you receive the amount you invested. Usually, the price of a previously issued bond rises when current interest rates fall. And a bond's price will fall when interest rates rise. Bonds are generally considered less risky than stocks, but they also offer lower potential returns.

Money Market Funds. Money market funds are short-term investments that usually act as a "parking place" for money between investments. These investments have the least risk of losing principal compared with stocks and bonds, but their potential returns are usually lower, so they may not beat inflation.

Although most mutual funds concentrate on one investment type, some funds hold a mix of investment types. For example, balanced funds mix stocks, bonds, and short-term investments so they're less risky than pure stock funds; however, they also offer a lower potential for return. Growth funds, on the other hand, invest in established companies whose stock values are expected to increase. Therefore, they carry more risk than balanced funds, but they also offer a higher potential for return.

The key to limiting your overall risk while producing more consistent investment returns is diversification. This simply means spreading your money among different investments. You benefit from automatic diversification when you invest in any of your plan's mutual funds because each of the funds holds a broad mix of many different securities. For instance, a well-diversified stock fund should not have a large loss if one of the many companies whose stock the fund holds has problems. You can diversify your retirement savings even more by investing in a selection of different funds that your plan offers. For example, you could spread your money among a stock fund, a bond fund, and a short-term fund.

In a 403(b) plan, you decide how much money you want to contribute to your account each pay period. Contributions are automatically deducted from your paycheck before taxes are taken out. The money is directed to a financial institution, or vendor, selected by your employer. Interest and earnings are free from taxes as long as the money remains in your account, so you have more real dollars working for you. When you withdraw the money-usually at retirement-you will have to pay taxes on the amount you take out of your account.

Although the money in your 403(b) account belongs to you, it isn't yours to spend. Remember, the point of participating in a 403(b) plan is to save for retirement, so the money is supposed to remain in your account until you're at least 59 ½ years old (past the early retirement penalty age). Your company's plan may allow you to take a loan from your account under certain circumstances, in which case you pay back the principal and current interest rates to your account over a set term. Some plans also allow for withdrawals under conditions of financial hardship. You should consider a hardship withdrawal only as a last resort, because this type of early withdrawal usually comes along with some financial penalties. (See "When can I withdraw money from my 403(b)?" below.

403(b)s work a lot like 401(k)s, but there are some significant differences. 401(k)s are retirement plans for employees of private and public for-profit organizations. 403(b)s, on the other hand, were created exclusively for employees of non-profit organizations. Additionally, investment options differ between the two types of plans.

Participating in a 403(b) plan is one of the best investments you can make in your future. Consider the following benefits:

- Your money grows in a tax-deferred environment. As long as your contributions remain in your 403(b) account, you don't have to worry about taxes taking a bite out of your retirement funds. Your account balance grows more quickly as a result.

- Your taxable income is reduced by your contributions. Because your contributions are automatically deducted from your paycheck before taxes are taken out, you'll be taxed on a smaller gross income. This means you won't have to pay as much in income tax.

- You can take the plan with you if you change jobs. If you decide to leave your current employer, you can take your 403(b) money with you. You may decide to make a rollover contribution into your new employer's 403(b) plan, or you may deposit the money into an Individual Retirement Account. (Note that 403(b) money cannot be rolled over into a 401(k) plan, however.) Either way you'll avoid the early withdrawal penalties you would have to pay if you took the money out as a lump sum.

- It's easy to keep track of the savings in your 403(b) account. You'll receive periodic statements from your employer that show your account balance, contributions, and any gains or losses on your investments. That way it's easy to keep an eye on how your retirement funds are growing.

The IRS limits the total amount of your pre-tax contributions over the year. The maximum amount that the IRS allows to be excluded from taxation is known as the maximum exclusion allowance (MEA). For the year 2013, this limit is the lesser of $17,500, which does not include any matching contributions to your account made by your employer. Your MEA is also determined by the following factors:

- your salary

- how many years you've worked for the company

- any tax-deferred contributions that you and your employer have made in prior years

If you haven't contributed the maximum allowance in previous years, a "catch-up" provision allows you to contribute an additional $3,000 each year going forward, up to a $15,000 lifetime maximum. This is especially helpful if you're close to retirement and you need to give your savings a boost. To qualify, you must have been employed at the same company for at least fifteen years.

Only employees of certain non-profit organizations-hospitals, colleges and universities, research institutes, libraries, and so forth-and K-12 public schools are eligible to contribute to a 403(b) plan. Under section 403(b)(12) of the IRS Tax Code, any employee who wants to contribute and is able to contribute at least $200 may participate in the program.

If you work for an eligible organization that does not have a 403(b) retirement plan, ask your employer or benefits representative about starting one.

Your organization's 403(b) plan may allow you to take a loan from your account, usually up to one-half of your account balance, not to exceed $50,000. You pay your account back the amount you borrowed, plus interest, through automatic deductions from your pay or bank account. Typically, employees are allowed five years to repay loans, and no taxes or penalties are incurred as long as the loan is repaid on time. If you don't repay your loan within this time frame, the loan is treated as a withdrawal, which is taxable. Not only must you pay current income taxes on the withdrawal, you must also pay a 10 percent early withdrawal penalty to the government.

Before you decide to take a loan from your account, you should consider how this will affect your retirement funds in the long term. Remember, the money can't grow for you if it's not in your account.

403(b)s are sometimes called tax-sheltered annuities (TSAs) because, in the past, the only investment options available to participants were annuities. An annuity is an insurance company contract that guarantees a series of payments over a specific period of time. Here's how it works: In the first phase of an annuity, known as the accumulation phase, you give money to the insurance company-either through periodic payments or in a lump sum-and the money earns a rate of return. As long as the money remains in the annuity, you don't pay taxes on any of it, including the interest. In the second phase, known as the annuitization phase, you begin receiving regular payments from your contract. These payments are subject to current income taxes. Also, if you make any withdrawals before age 59 ½, you'll have to pay a 10 percent early withdrawal penalty to the government, since the money in your 403(b) is really intended as retirement savings.

Some annuities offer a death benefit, meaning that if you die before the annuitization phase, your beneficiary will receive the greater of either the current value of your annuity or the amount you have paid into it. Once you begin to receive monthly payments, you are no longer eligible for this benefit. However, you can buy a "term certain" annuity, which means that payments to you or your beneficiary are guaranteed for a certain period of time-for example, ten or fifteen years.

The two basic types of annuities are deferred annuities and immediate annuities. When you buy a deferred annuity, your payments from the insurance company are postponed until a given date in the future. When you buy an immediate annuity, you begin to receive payments right away. It's important to note that a deferred annuity can be bought through periodic payments or in a lump sum, while an immediate annuity can be bought only with a single payment.

In addition to being classified as either deferred or immediate, annuities are either fixed or variable. A fixed annuity pays a fixed rate of return on your money. It's the insurance company's responsibility to invest your money so it produces this guaranteed rate of return. Since the payout is guaranteed, fixed annuities are considered to be low risk. The downside is that rising inflation can erode the earning power of a fixed annuity.

Since you know that a fixed annuity pays a fixed rate of return, you've probably figured out that a variable annuity pays a variable rate of return. In a variable annuity, your money goes into subaccounts. You decide how to allocate your money among the available investments options within the subaccounts, such as stocks, bonds, and money market accounts. Depending on the performance of your investments, you may get a higher rate of return than you would if you put your money in a fixed annuity. However, if your investments perform poorly, then the rate of return on your money could decrease dramatically.

These days, 403(b) participants are often allowed to invest in mutual funds, as well as annuities. Mutual funds contain investments such as stocks, bonds, and money market funds. When you buy shares in a mutual fund, you invest in all the securities (investments) in that fund. It's up to you to divide your money among the securities within the fund. (For more information on stocks, bonds, and money market funds, see "What investment options are available to 401(k) participants?" above.)

Since the point of participating in a 403(b) plan is to save for retirement, the money is supposed to remain in your account until you're at least 59 ½ years old (past the early retirement penalty age). If you make a withdrawal before you reach this age, you'll have to pay current income taxes on the withdrawal, plus a 10 percent early withdrawal penalty to the government.

Some plans also allow for withdrawals under conditions of financial hardship, but you must prove that you have an "immediate and heavy financial need" and that you don't have "any other resources resonably available to you to handle that financial need." And you'll still have to pay taxes on the money you withdraw, as well as the 10 percent penalty. The IRS allows withdrawals for the following:

- unreimbursable medical expenses for you, your spouse, or your dependents

- purchase of a primary residence

- payment of college tuition and related educational expenses

- payments necessary to prevent eviction from your home, or foreclosure on the mortgage of your primary residence

There are only a few cases in which the IRS won't charge the 10 percent early withdrawal penalty, although you'll still have to pay income taxes. The 10 percent penalty may be waived if:

- your unreimbursable medical expenses exceed 7.5 percent of your income

- you're separated from service at 55 years of age or older

- you're totally disabled

- you've died and the money goes to your beneficiary

US Non-Qualified Plans

Generally, a nonqualified deferred compensation plan is an agreement or promise by an employer to its employees to pay compensation to the employees at some future date.

Historically, nonqualified deferred compensation plans have been established to supplement the retirement benefits provided to a select group of management or highly compensated employees (HCEs) under qualified deferred compensation plans. However, nonqualified deferred compensation plans have also become more attractive and more important in retirement planning because of the following:

- changes in the U.S. law regarding qualified plans

- limitations on contributions to qualified plans

- restrictive discrimination and participation rules

- complicated rules involved in maintaining and operating these plans

Typically, nonqualified deferred compensation plans are designed to benefit the following:

- key executives,

- a select group of management or highly compensated employees, and

- employees whose benefits ordinarily would be limited under U.S. Code Section 415.

Yes, there are several types. Let FMi help you decide which one is best for your company.

Yes, an escrow account or a trust may be established to enable the employer to fulfill its promise to the employee. There are two basic types of trusts that may be used by the employer:

Rabbi trust: An irrevocable trust that is established for the benefit of the employee but that is subject to the claims of the employer's general creditors.

Secular trust: An irrevocable trust that is established for the benefit of the employee who has a nonforfeitable right to the funds and that is protected from the employer and the employer's creditors but is taxable to the employee.

Yes, a company may purchase insurance policies to fund its promise. These policies are referred to as corporate-owned life insurance (COLI).

Nonqualified deferred compensation plans generally are "unfunded" plans. An unfunded plan is merely a promise by the employer to pay the employee compensation at some future date. However, a nonqualified deferred compensation plan may also be a "funded" plan.

Whether or not a plan is "funded" or "unfunded" generally requires an examination of the surrounding facts and circumstances.

Funded plans: A plan is usually considered "funded" if an amount is irrevocably placed with a third party for the benefit of an employee and neither the employer nor its creditors has any interest in this amount.

Unfunded plans: An "unfunded" plan is merely an unsecured promise by an employer to pay compensation to an employee at some future date. The employer may set aside assets in order to fulfill its promise to the employee, but the assets that are set aside must remain part of the employer's general assets and subject to the claims of the employer's creditors.

Yes. If a plan is funded, the plan will generally have to satisfy the requirements contained in Title I of ERISA, which pertains to participation and vesting, funding, and fiduciary requirements. If a plan is unfunded, it may be exempt from these requirements.

Yes. Generally, contributions to an unfunded plan are not deductible by an employer and are not includable in an employee's income until some future date when the benefits are distributed or made available to the employee. Contributions to a funded plan are generally deductible by the employer and includable in an employee's income in the year the contribution is made.

Amounts contributed to a nonqualified deferred compensation plan are generally includable in the employee's gross income at the time these amounts are paid or made available to the employee.

Generally, no. If the employee's control over the contributions is subject to substantial limitations, then contributions to a nonqualified deferred compensation plan should not be subject to the constructive receipt doctrine. Generally, the employee, as a cash method taxpayer, includes amounts in gross income when they are actually or constructively received. Generally, income, although not actually reduced to a taxpayer's possession, is constructively received by the taxpayer in the taxable year during which it is:

- credited to his or her account

- set apart for him or her, or

- otherwise made available to the taxpayer

However, income is not constructively received if the taxpayer's control of its receipt is subject to substantial limitations or restrictions. Accordingly, if a corporation credits it employees with bonus stock, but the stock is not available to the employees until some future date, the mere crediting on the books of the corporation does not constitute receipt.

Generally, no. If contributions are made or amounts set aside in accordance with a nonqualified deferred compensation plan are subject to the claims of the employer's general creditors, then such contributions or amounts should not be subject to the economic benefit doctrine. If, on the other hand, contributions to the plan are protected from the employer's creditors and the rights of the participating employees to the benefits provided under the plan are nonforfeitable, the economic benefit doctrine should apply and the contributions would be includable in the participating employee's income.

Under the economic benefit doctrine, if any economic or financial benefit is conferred on an individual as compensation in a taxable year, it is taxable to the individual in that year.

A rabbi trust is a trust established by an employer to assist the employer in satisfying its obligation to employees under one or more nonqualified deferred compensation plans. The trust is commonly referred to as a rabbi trust because the first Internal Revenue Service (IRS) letter ruling regarding this type of trust was issued to a rabbi.

The employer establishes a rabbi trust by entering into a trust agreement with a trustee.

A common purpose for establishing a rabbi trust is to provide comfort to participants that their respective benefits under the unfunded deferred compensation plan will not be endangered by an unfriendly takeover of the employer or any other unfriendly change in the management of the employer. The assets in the trust will be subject to some risk, however, because the assets must be subject to the claims of the employer's creditors in the event of bankruptcy or insolvency.

A rabbi trust may also be established to ensure that assets will be available for distribution to participating employees, thereby reducing or eliminating a financial strain on the employer when it comes time for distributions to occur.

A third purpose is to provide a vehicle for making diversified investments of deferred amounts and for allocating the earnings to separate accounts maintained for the participants.

Yes. A rabbi trust may be established in connection with a deferred compensation plan that permits more than one employee to benefit under the plan or in connection with a series of deferred compensation agreements with employees.

No. The Department of Labor (DOL) has stated that the transfer of assets to a rabbi trust does not cause a nonqualified deferred compensation plan to be funded.

Yes. If a plan is funded, it generally will have to satisfy the requirements contained in Title I of ERISA, pertaining to participation and vesting, funding, and fiduciary requirements. If a plan is unfunded the plan may be exempt from these requirements.

Generally, unfunded deferred compensation plans maintained by an employer primarily for the benefit of a select group of management or highly compensated employees (e.g. top-hat plans) are exempt from the participation and vesting, funding, and fiduciary responsibility parts of Title I of ERISA. These unfunded plans are not exempt from the reporting and disclosure requirements of Part 1 of Title I of ERISA. However, DOL regulations contain an alternative method of compliance with these plan requirements. Under these regulations, the reporting and disclosure requirements will be satisfied by filing a statement with the Secretary of Labor containing information identifying the plan. An excess benefit plan as defined under ERISA Section 3(36) that is unfunded is exempt for all ERISA Title I and Title IV provisions.

Yes. The IRS will issue favorable rulings on rabbi trusts that are used in connection with nonqualified deferred compensation plans.

No. Although obtaining a favorable ruling from IRS will provide taxpayers with some comfort in determining their tax liability with respect to a rabbi trust, favorable tax treatment can be established without a ruling.

The IRS will apply the following general guidelines when reviewing a rabbi trust agreement:

- Establishment: The establishment of a rabbi trust must be a voluntary decision on the part of the employer. The participants should not be parties to the trust agreement in any respect.

- Trustee: The IRS generally requires, at least, that the trustee is independent from all participants.

- Status Under ERISA: The trust must provide that it is the intention of the parties that the plan and trust arrangement are unfunded for tax purposes and for purposes of Title I of ERISA.

- Trust Assets: The trust must provide that the assets of the trust shall be made available to satisfy the claims of the employer's general creditors in the event of bankruptcy or insolvency.

- Bankruptcy: The trust must define bankruptcy as when the employer is subject as a debtor to a pending proceeding under the Federal Bankruptcy Code.

- Insolvency: The trust must define insolvency as when the employer is unable to pay debts as they mature.

- Notice: The trust must provide that the board of directors and the chief executive officer of the employer shall give the trustee prompt written notice of bankruptcy or insolvency.

- Trustee's Duty: The trust must provide that upon the trustee's receipt of the notice from the employer, or if the trustee has actual knowledge of bankruptcy or insolvency, the trustee shall stop making payments to plan participants or beneficiaries.

- Nature of the Obligation: The trust must provide that a participant/beneficiary has only the employer's unfunded, unsecured promise to pay benefits under the plan, and the status of an unsecured general creditor.

- Nonassignability: The trust must provide that a participant/beneficiary's rights to benefits are not subject in any manner to anticipation, alienation, sale, transfer, assignment, pledge, or encumbrance.

- Other Triggering Events: The IRS will not rule with respect to any "triggering events" in the trust that trigger or accelerate the payment of benefits under the plan. For example, a trust that provides for an acceleration of benefits upon termination of the trust is unacceptable. However, an acceleration of benefits upon termination of the plan may be acceptable.

- Funding: The trust must provide that the employer may fund the trust at its discretion.

- Termination: The trust may provide for a termination of the trust. If so, the trust must provide that assets will be transferred back to the employer, and participants will be paid benefits as they become eligible, under the plan.

The IRS will apply the following general guidelines when reviewing a nonqualified compensation plan used in conjunction with a trust agreement:

- Initial Election: If an arrangement provides for an election to defer payment of compensation, the election must be made before the beginning of the period of service for which the compensation is payable regardless of any forfeiture provision in the arrangement.

- Subsequent Elections: If a plan provides for an election other than the initial election to defer compensation, such subsequent elections must either be made prior to the beginning of the period of service to which the deferred compensation relates or contain a substantial forfeiture provision that remains in effect throughout the entire period of deferral.

- Change in Amounts Deferred: If a plan provides for an election to change the amount deferred, the election must be made before the period of service during which the compensation is to be earned. This should be done on a yearly basis. A plan may permit a participant to revoke his or her election to defer, but such revocation must be done with respect to amounts yet to be earned and the plan must provide that the participant may not elect to defer again until the next calendar year.

- Payment of Benefits: The plan must specifically provide what event(s) will trigger the commencement of benefits, how soon benefits will actually commence after the triggering event, and in what form and amount they will be paid.

- Triggering Events: The IRS will rule on plans that provide benefits upon retirement (normal, early, or late), death, disability (complete and permanent), termination and employment, unforeseeable emergency of the participant, or termination of the plan.

- Benefit Commencement: The plan must state when benefits will commence after the triggering event.

- Emergency Withdrawal Provisions: The plan may permit an in-service distribution if the participant experiences an unforeseeable emergency that meets the requirements.

- Investment Discretion: The IRS will rule with respect to a plan that permits a participant to choose investments. Also, a plan may provide that a participant can change the investment of amounts already deferred. This will not be treated as a subsequent election. The plan should provide, however, that the employer shall at all times be the owner and beneficiary of assets held for the participant.

- Nature of the Obligation: The plan must provide that a participant/beneficiary has only the employer's unsecured promise to be paid and the status of a general unsecured creditor.

- Nonassignability: The plan must provide that a participant/beneficiary's rights under the plan are not subject in any manner to anticipation, alienation, sale, transfer, assignment, pledge, or encumbrance.

- Termination: A plan may provide for an acceleration of benefits in the event of a termination of the plan so long as: everyone is paid benefits in the same manner, and participants may not control the decision as to whether a plan should be terminated.

No. The assets held in a rabbi trust are owned by the employer and are subject to the claims of the employer's general creditors.

Employees have very limited rights to the assets held on their behalf in a rabbi trust. Generally, the rights of any employee to the benefits under the rabbi trust, prior to the actual receipt of such benefits, are limited to those of a general unsecured creditor of the employer.

Generally, the employer is treated as the owner of the rabbi trust.

Yes. An employer must include the trust income, deductions, and credits when calculating its income tax liability because the employer is treated as the grantor and the owner of the trust.

Employers can deduct the amounts paid or made available pursuant to a nonqualified plan in the year in which the amounts are includable in the gross income of the recipient, but only to the extent such payments are ordinary and necessary business expenses.

The funds held in a rabbi trust are includable in the gross income of the employee (or the employee's beneficiary) when the benefits are paid or made available (i.e. no limitations or restrictions) to the employee.

No. Contributions to a rabbi trust should not be subject to the constructive receipt doctrine if the employee's control over the contributions is subject to substantial limitations. Generally, the employee, as a cash method taxpayer, includes amounts in gross income when they are actually or constructively received. Generally, income, although not actually reduced to a taxpayer's possession, is constructively received by the taxpayer in the taxable year during which it is:

- credited to his or her account,

- set apart for him or her, or

- otherwise made available to the taxpayer.

However, income is not constructively received if the taxpayer's control of its receipt is subject to substantial limitations or restrictions. The funds held in a rabbi trust must at all times be subject to the claims of the employer's creditors. Thus, the creation of the trust will not result in constructive receipt by the employees of the amounts the employer contributes to the trust.

No. Contributions to a rabbi trust should not be includable in the participating employee's income under the economic benefit doctrine because the funds held in a rabbi trust are owned by the employer and are subject to the claims of the employer's general creditors.

Under the economic benefit doctrine, if any economic or financial benefit is conferred on an individual as compensation in a taxable year, it is taxable to the individual in that year.

Yes. According to the IRS, the trustee may invest "in securities (including stock or rights to acquire stock) or obligations issued" by the employer.

Learning Center

Learning Center